I ran my hand over the rusting rivets as a ritual of remembrance and reverence for the women, the “Rosies,â€Â that changed the course of history in the Kaiser shipyards of Richmond and San Francisco as well as in many munitions factories throughout the country. One of the last remaining Victory Ships, the Red Oak, is docked at Richmond’s port #3 while it is slowly and lovingly being restored by volunteers, some of whom had actually served years ago as crew on the Red Oak or one of the other wartime ships. They remember vividly how, after the ships’ “champagne baptism,†they headed out to Europe or the South Pacific.

I ran my hand over the rusting rivets as a ritual of remembrance and reverence for the women, the “Rosies,â€Â that changed the course of history in the Kaiser shipyards of Richmond and San Francisco as well as in many munitions factories throughout the country. One of the last remaining Victory Ships, the Red Oak, is docked at Richmond’s port #3 while it is slowly and lovingly being restored by volunteers, some of whom had actually served years ago as crew on the Red Oak or one of the other wartime ships. They remember vividly how, after the ships’ “champagne baptism,†they headed out to Europe or the South Pacific.

The Red Oak, like other remaining relics from that era, is now dressed in rust, fraying rope, and rivets decorated with multiple layers of pealing paint. As the very informative visitor center reminds us, every rusting hinge and aging anchor testifies to the fact that more than six million female workers helped to build the ships, planes, bombs, tanks and other weapons that would eventually win World War II.

The Red Oak, like other remaining relics from that era, is now dressed in rust, fraying rope, and rivets decorated with multiple layers of pealing paint. As the very informative visitor center reminds us, every rusting hinge and aging anchor testifies to the fact that more than six million female workers helped to build the ships, planes, bombs, tanks and other weapons that would eventually win World War II.

These women stepped up to the plate without wavering and gave up their home lives to accomplish the jobs previously identified as “men’s work.” Every day during the war, women, both young and old, black and white, would punch into work at the shipyards, factories and munitions plants, breaking gender and racial barriers and increasing the workforce by 50 percent. An entirely new image of women in American society was created, setting the stage for upcoming generations.

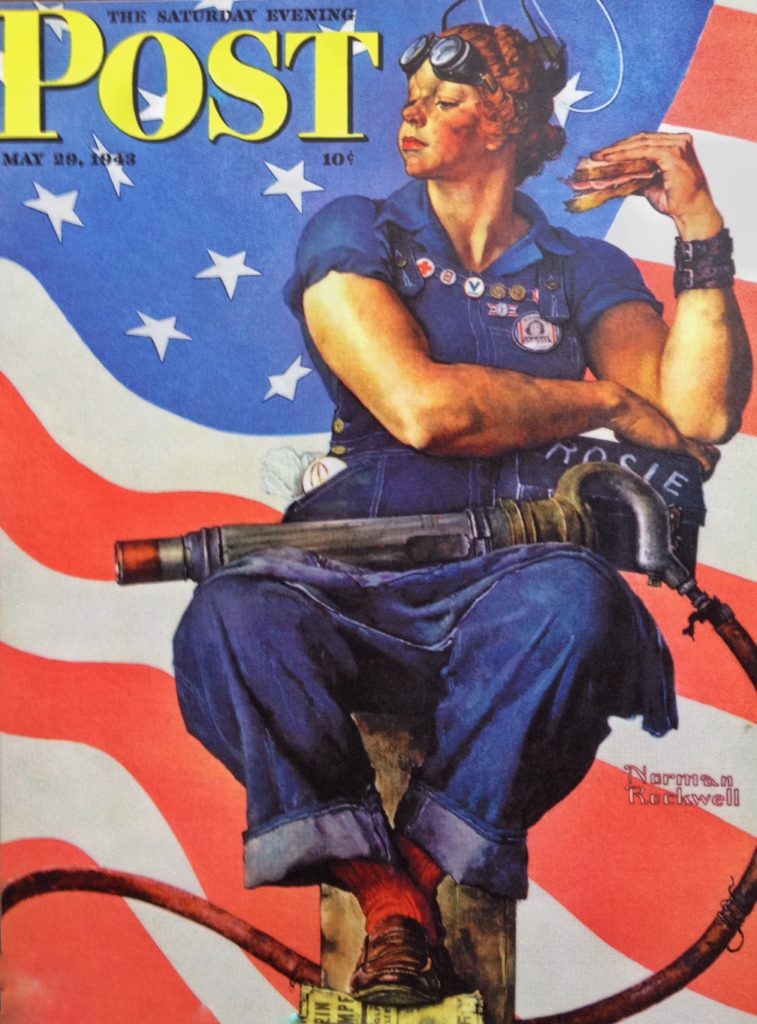

Rosie the Riveter’s first mention was in a song written by Redd Evans and John Jacob Loeb in 1942. The lyrics were being sung throughout the country and told the true story: “That little frail girl can do more than a man can do.” Yes, some were actually better at certain tasks, although women war-workers were paid only 60 percent of male wages. The PR front for the government propaganda machine “Rosie the Riveter†was modeled after a real person. Her name was Rosie Will Monroe who helped build B24 bombers.

I met my first group of Rosie the Riveters in 1989 when I moved to Richmond, California, to be the pastor of Grace Lutheran Church. These women came alone or with families from Minnesota, South Dakota and Arkansas, and I wish now that I had recorded their stories.

I met my first group of Rosie the Riveters in 1989 when I moved to Richmond, California, to be the pastor of Grace Lutheran Church. These women came alone or with families from Minnesota, South Dakota and Arkansas, and I wish now that I had recorded their stories.

By the time I talked with Matilda she wasn’t quite sure what she had for lunch the day before, but she recalled the minute details of a particular day in February, 1943 — the smells, the sounds of the swelling sea, and the cool fingers of the fog as it rolled in at 4:59 PM.. She was welding high up on a liberty ship, and the end-of-the-shift whistle blew as it always did, a few seconds early “so we could put away our tools, gather up our lunch boxes and head for the bus stop to return to downtown Richmond to make dinner for our children.â€

Matilda’s women workmates, for safety’s sake, had tied her in place in the late afternoon for the last welding job high above the ship’s master quarters. But when that whistle blew they forgot to retrieve her. Matilda watched them as they walked out of the shipyard gate. From her perch she shouted, “Hey, get me down from here.†But there she stayed until one of her friends, already on the homeward bound bus, missed her and asked her companions, “Is Matilda still tied into the welding hold?â€Â Even though it would cost them extra bus money, a couple of them returned to rescue her. Matilda told me that she loved her job – despite the occasional mishaps, sexual harassment and the very hard work. She welded together some 20 different liberty ships, boasting that she and the girls “won the war and changed the world.â€

Matilda’s women workmates, for safety’s sake, had tied her in place in the late afternoon for the last welding job high above the ship’s master quarters. But when that whistle blew they forgot to retrieve her. Matilda watched them as they walked out of the shipyard gate. From her perch she shouted, “Hey, get me down from here.†But there she stayed until one of her friends, already on the homeward bound bus, missed her and asked her companions, “Is Matilda still tied into the welding hold?â€Â Even though it would cost them extra bus money, a couple of them returned to rescue her. Matilda told me that she loved her job – despite the occasional mishaps, sexual harassment and the very hard work. She welded together some 20 different liberty ships, boasting that she and the girls “won the war and changed the world.â€

The rust and the ropes and the rivets are witnesses to Matilda’s efforts and the efforts of millions of women who endured a misogynistic work culture, racial abuse and inequities to pave the way toward a new appreciation of American women. There was growing hope among the 18 million women or more who entered the overall work force during the war that, when the war was over, life and society would never be the same again.

One day, they believed, women would be treated with respect, valued for their skilled work, and know the dignity that belongs to every human being. In fact, Matilda confessed to me that she once prayed the war would not end so she could march off to work each morning and return with her head held high and a paycheck in her purse. During those days she dreamed that eventually a woman would become president. Her “we can do it†generation ended up being the “we have done it†icons of hope.

One day, they believed, women would be treated with respect, valued for their skilled work, and know the dignity that belongs to every human being. In fact, Matilda confessed to me that she once prayed the war would not end so she could march off to work each morning and return with her head held high and a paycheck in her purse. During those days she dreamed that eventually a woman would become president. Her “we can do it†generation ended up being the “we have done it†icons of hope.

The “Rosies†never faltered. They had changed the industry and left permanent effects. By “permanent effects,” I don’t mean the rust, fraying ropes and discolored rivets of the Red Oak and similar ships. We who follow in their steps and are alive today are part of the permanent effects as we step up to the plate knowing what we must do to honor and realize Matilda’s dream and the aspirations of our world-changing “Rosie Foremothers!”

The “Rosies†never faltered. They had changed the industry and left permanent effects. By “permanent effects,” I don’t mean the rust, fraying ropes and discolored rivets of the Red Oak and similar ships. We who follow in their steps and are alive today are part of the permanent effects as we step up to the plate knowing what we must do to honor and realize Matilda’s dream and the aspirations of our world-changing “Rosie Foremothers!”

All above images are details on the Red Oak Victory Ship. The Rosie to the right is by Norman Rockwell for the May, 1943 Saturday Evening Post.