It’s almost miraculous that so many African animals manage to eke out an existence in the arid, desert-like environment of Namibia — elephants, lions, cheetah, rhinos, oryx and wild horses to name a few. We can be sincerely thankful that Namibia’s progressive, community-based approach to conservation protects so much wildlife by providing hundreds of square miles of sanctuary and poaching-free zones.

It’s almost miraculous that so many African animals manage to eke out an existence in the arid, desert-like environment of Namibia — elephants, lions, cheetah, rhinos, oryx and wild horses to name a few. We can be sincerely thankful that Namibia’s progressive, community-based approach to conservation protects so much wildlife by providing hundreds of square miles of sanctuary and poaching-free zones.

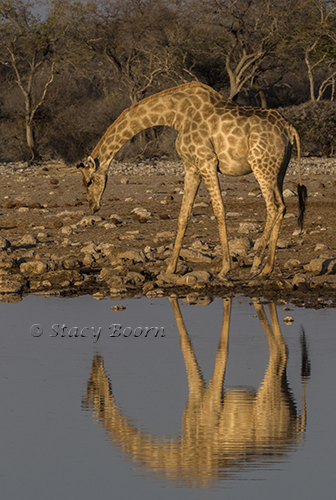

In the vast flagship of the Namibian park system, Etosha National Park, you will find an out-and-out profusion of wildlife around the numerous waterholes. Here the magic happens, whether it’s a herd of elephants filling their trunks with water, a rhino reflected in the water by the light of a full moon, or a giraffe reaching down for a drink with its legs splayed like a circus performer.

Etosha National Park is one of the world’s premier wildlife reserves. The size of Switzerland, Etosha is a semi-arid savannah, with grassland and thorn scrub surrounding a flat saline desert pan, a calcium-rich, impermeable earthen crust. The name Etosha is variously translated ‘Place of Mirages’, ‘Land of Dry Water’ or ‘Great White Place’.

Etosha National Park is one of the world’s premier wildlife reserves. The size of Switzerland, Etosha is a semi-arid savannah, with grassland and thorn scrub surrounding a flat saline desert pan, a calcium-rich, impermeable earthen crust. The name Etosha is variously translated ‘Place of Mirages’, ‘Land of Dry Water’ or ‘Great White Place’.

Although dry and dusty, Etosha Park is a haven for 114 kinds of mammals and 340 bird species. Some of the stars of Etosha are its endemic black-faced impala and elephants. These elephants are huge, the tallest in Africa, measuring up to 14 feet at the shoulder; they are awe-inspiring to see even though mineral deficiencies and their habit of digging for water result in short tusks. The resident giraffe belong to a subspecies found only in the park and in north-western Namibia.

Although dry and dusty, Etosha Park is a haven for 114 kinds of mammals and 340 bird species. Some of the stars of Etosha are its endemic black-faced impala and elephants. These elephants are huge, the tallest in Africa, measuring up to 14 feet at the shoulder; they are awe-inspiring to see even though mineral deficiencies and their habit of digging for water result in short tusks. The resident giraffe belong to a subspecies found only in the park and in north-western Namibia.

To give a sense of just how easy it to escape from “the world†in Namibia, compare it with Germany, its former colonial ruler. Namibia is twice the size of Germany, but, while Germany has a total population in excess of 80 million, Namibia’s human population is just a tad over two million.

Okaukuejo, the first tourist camp inside Etosha Park, was built beside a well-established waterhole, now the main feature of the camp. All day and into the flood-lit early hours of the night, an orderly parade of animals come to the waterhole. Visitors can sit in comfort inside the camp with only a low wall between them and herds of elephants, rhinos and even a pride or two of lions gulping the thirst-slaking liquid.

Okaukuejo, the first tourist camp inside Etosha Park, was built beside a well-established waterhole, now the main feature of the camp. All day and into the flood-lit early hours of the night, an orderly parade of animals come to the waterhole. Visitors can sit in comfort inside the camp with only a low wall between them and herds of elephants, rhinos and even a pride or two of lions gulping the thirst-slaking liquid.

Shortly after dusk on our first evening we witnessed 10 elephants slowly marching toward the waterhole. In the distance, other animals stood still and watched the elephants slurp and splash in the pool’s water for about 10 minutes before they finally sauntered off in the opposite direction. Then, group by group, the other animals would take their turn, drinking only after spying out the horizon to check for possible danger. It was like a slow-motion video – the zebras went to the water’s edge, then the giraffes followed by the rhinos. Awesome!

It was as if I were standing some 50 feet away from a menagerie-carousel come alive, each row of animals slowly sliding off the revolving floor and finding its way to this pool of water, so unique and precious in the otherwise dry and rocky terrain. No calliope was playing; there was only the sound of swooping birds, a few jackal grunts and the scuffling of soft-padded feet, but it was more magical and lovely than any orchestra could play, music of the night.

It was as if I were standing some 50 feet away from a menagerie-carousel come alive, each row of animals slowly sliding off the revolving floor and finding its way to this pool of water, so unique and precious in the otherwise dry and rocky terrain. No calliope was playing; there was only the sound of swooping birds, a few jackal grunts and the scuffling of soft-padded feet, but it was more magical and lovely than any orchestra could play, music of the night.

The large mammals in Etosha National Park include lion, leopard, elephant, rhino, giraffe, wildebeest, cheetah, hyena, mountain and plains zebra, springbok, impala, kudu, oryx and eland. Among the smaller species one can find the dik-dik, black-back jackal, bat-eared fox, warthog, honey badger and ground squirrel. Except for the leopard, hyena and honey badger, we saw all these and, of course, dozens of different birds.

The large mammals in Etosha National Park include lion, leopard, elephant, rhino, giraffe, wildebeest, cheetah, hyena, mountain and plains zebra, springbok, impala, kudu, oryx and eland. Among the smaller species one can find the dik-dik, black-back jackal, bat-eared fox, warthog, honey badger and ground squirrel. Except for the leopard, hyena and honey badger, we saw all these and, of course, dozens of different birds.

If one needs concrete proof that human beings are not the center of the universe, a few days in Etosha will put things in perspective. We need to learn from our fellow-inhabitants on this planet. The straight and twisted antlers of the many “antelopes,†for instance, reach sun-ward and point our gaze in new directions! The animals at the edge of the “Great White Place†grace us with a greater attitude of reverence and appreciation for all creatures large and small. (Image: Oryx calf tries out new legs)

What a life-enhancing delight it was to ride the carousel of creation in Namibia!

What a life-enhancing delight it was to ride the carousel of creation in Namibia!

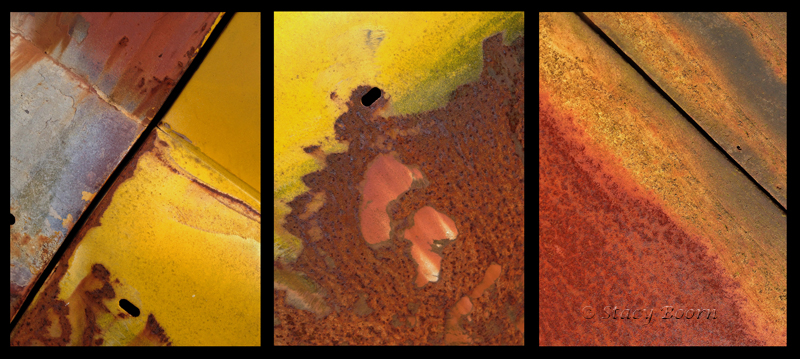

The weather’s initial cool, dark welcome added to the sense of abandonment and eeriness that seemed to be wandering like a ghost through the collapsing buildings of this once-luxurious town. The sands of immense dunes now make their way through the open doors and broken windows, recapturing their original footholds and burying the evidence of the short-lived glory days.

The weather’s initial cool, dark welcome added to the sense of abandonment and eeriness that seemed to be wandering like a ghost through the collapsing buildings of this once-luxurious town. The sands of immense dunes now make their way through the open doors and broken windows, recapturing their original footholds and burying the evidence of the short-lived glory days. Kolmanskop was built when diamonds were discovered there in 1908. It became home to hundreds of German miners desperately seeking their fortune in the Namibian desert. The shells of the once-active town businesses, hospital, school, gymnasium, and theater, as well as huge individual houses for engineers, doctors, and architects have all fallen silent. The family flats, each room painted a different pastel color with decorative borders, are now swathed in sand.

Kolmanskop was built when diamonds were discovered there in 1908. It became home to hundreds of German miners desperately seeking their fortune in the Namibian desert. The shells of the once-active town businesses, hospital, school, gymnasium, and theater, as well as huge individual houses for engineers, doctors, and architects have all fallen silent. The family flats, each room painted a different pastel color with decorative borders, are now swathed in sand. Toward the end of the 20th century some buildings such as the casino, skittle alley and retail shop were restored. One can only enter the town with a permit — our permit was good from sunrise to sunset and, except for a few small groups in the morning, this ghost town was all ours.

Toward the end of the 20th century some buildings such as the casino, skittle alley and retail shop were restored. One can only enter the town with a permit — our permit was good from sunrise to sunset and, except for a few small groups in the morning, this ghost town was all ours. “Surrender to the desert” is the chant of the winds and the echo of the drifting sands. I wonder if this will be the same song in 20 years at Oranjemund, the still-active diamond mine located in the southern part of the country near the South African border. Namdeb Diamond Corporation operates the huge alluvial workings; it is so successful, it has made Namibia the world’s fifth-largest diamond supplier.

“Surrender to the desert” is the chant of the winds and the echo of the drifting sands. I wonder if this will be the same song in 20 years at Oranjemund, the still-active diamond mine located in the southern part of the country near the South African border. Namdeb Diamond Corporation operates the huge alluvial workings; it is so successful, it has made Namibia the world’s fifth-largest diamond supplier. My next blog will include some of my favorite Namibian treasures: photos of the wild animals. Oryx, Springbok, Giraffe and others will probably make the lineup.

My next blog will include some of my favorite Namibian treasures: photos of the wild animals. Oryx, Springbok, Giraffe and others will probably make the lineup. I could not live like the Himba people. Their small, clan-based villages dot the harsh and barren lands of north western Namibia. For thousands of years they have been carrying on the same routine. In the morning the cows are milked, and then the men, goats and cattle go off to find grazing lands. Nomadic people, they sometimes occupy 10 different village sites in one year. As harsh as their lifestyle is and as unaffected by modern ideologies, they seem to be extremely peaceful and happy.

I could not live like the Himba people. Their small, clan-based villages dot the harsh and barren lands of north western Namibia. For thousands of years they have been carrying on the same routine. In the morning the cows are milked, and then the men, goats and cattle go off to find grazing lands. Nomadic people, they sometimes occupy 10 different village sites in one year. As harsh as their lifestyle is and as unaffected by modern ideologies, they seem to be extremely peaceful and happy. Most Himba villages are small and made up of extended family units. When visiting such a village one must ask permission from the chief, but our afternoon visit found no chief on site so his three wives welcomed us.

Most Himba villages are small and made up of extended family units. When visiting such a village one must ask permission from the chief, but our afternoon visit found no chief on site so his three wives welcomed us. The Himba women were very concerned for us because we were mostly a party of women without spouses or children. They wondered how we could possibly survive without these helpers to take care of the daily tasks. After additional conversation they seemed more pleased than perplexed with our life choices.

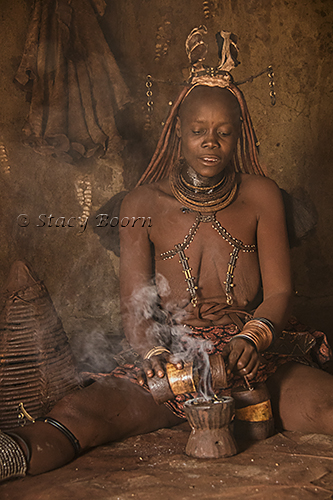

The Himba women were very concerned for us because we were mostly a party of women without spouses or children. They wondered how we could possibly survive without these helpers to take care of the daily tasks. After additional conversation they seemed more pleased than perplexed with our life choices. In one large round hut we witnessed how the women perfume themselves with bellowing incense. They explained who lives in the hut and how the family units worked. At age of three the children leave the parent’s hut to live with all the village children where they grow up playing and caring for one another. The children are raised by everyone in the village. Their hairstyles give away whether the child is a boy or girl – two braids down the front of the face indicate a girl.

In one large round hut we witnessed how the women perfume themselves with bellowing incense. They explained who lives in the hut and how the family units worked. At age of three the children leave the parent’s hut to live with all the village children where they grow up playing and caring for one another. The children are raised by everyone in the village. Their hairstyles give away whether the child is a boy or girl – two braids down the front of the face indicate a girl. The head of the village is the oldest male member of the family groups. He is responsible for the religious organization of the village, the sacred acts, solving problems, overseeing life and the dispensing of justice.

The head of the village is the oldest male member of the family groups. He is responsible for the religious organization of the village, the sacred acts, solving problems, overseeing life and the dispensing of justice. I don’t usually photograph people, but I love to take people-shots when I’m traveling, especially in places where I cannot speak the native language. My camera becomes a vehicle of communication. Photographing others is almost like a dance that we enter into – smiling and looking at one another and making gestures. With the group of Himba children I realized that not all hand signals are interpreted in the same way. I was trying to get them to look in a certain direction. I put my hand above my head hoping their eyes would go there, but instead they kept waving back at me.

I don’t usually photograph people, but I love to take people-shots when I’m traveling, especially in places where I cannot speak the native language. My camera becomes a vehicle of communication. Photographing others is almost like a dance that we enter into – smiling and looking at one another and making gestures. With the group of Himba children I realized that not all hand signals are interpreted in the same way. I was trying to get them to look in a certain direction. I put my hand above my head hoping their eyes would go there, but instead they kept waving back at me.

On the west coast of southern Africa, the country of Namibia is vast and mostly desolate. Bisected by the Tropic of Capricorn (we stopped at the sign), its western border is the icy Atlantic Ocean. In the east, it is bordered by the Kalahari Desert. Yet it is a land of magnificent beauty — towering sand dunes, jagged mountains, geological wonders (including diamond mines), wild animals, ancient tribes and botanical marvels.

On the west coast of southern Africa, the country of Namibia is vast and mostly desolate. Bisected by the Tropic of Capricorn (we stopped at the sign), its western border is the icy Atlantic Ocean. In the east, it is bordered by the Kalahari Desert. Yet it is a land of magnificent beauty — towering sand dunes, jagged mountains, geological wonders (including diamond mines), wild animals, ancient tribes and botanical marvels.

and I have come to believe this after laughing with women in a Himba village and doing my own dance in the desert dunes trying to shake off a lizard that had crawled up my pant leg. (pictured here). I survived that episode, but the sights and experience of Namibia as a whole will be with me forever.

and I have come to believe this after laughing with women in a Himba village and doing my own dance in the desert dunes trying to shake off a lizard that had crawled up my pant leg. (pictured here). I survived that episode, but the sights and experience of Namibia as a whole will be with me forever.

San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts is a stunning historic landmark. Modeled after classic Greco-Roman architecture, the palace was built as a temporary structure for the 1915 Pan-American Exhibition. It stood for decades until it was reconstructed with more permanent materials in 1967. In addition, the landscape around it is breathtaking in its beauty, showcasing a wonderful variety of plant and animal life. I am especially moved by the gorgeous swans that make the palace pond their home.

San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts is a stunning historic landmark. Modeled after classic Greco-Roman architecture, the palace was built as a temporary structure for the 1915 Pan-American Exhibition. It stood for decades until it was reconstructed with more permanent materials in 1967. In addition, the landscape around it is breathtaking in its beauty, showcasing a wonderful variety of plant and animal life. I am especially moved by the gorgeous swans that make the palace pond their home. Last week just one swanling, now a hardy juvenile, was still swimming with its parents. Volunteers on the palace grounds say that, while the disappearance of the chicks was sad, the young ones would probably have been killed by their father come mating time. Despite all this drama, the beauty and lure of the swans are still very empowering.

Last week just one swanling, now a hardy juvenile, was still swimming with its parents. Volunteers on the palace grounds say that, while the disappearance of the chicks was sad, the young ones would probably have been killed by their father come mating time. Despite all this drama, the beauty and lure of the swans are still very empowering.

If I had been near a volcano, I would have been convinced that the white shapes ascending into the sky were the prelude of a large scale eruption. But I was in the middle of flat, uncultivated farmland. My first sighting was from a distance, and I could not identify what was happening. It was late afternoon, and the light was coming from a low side angle. Then, all of a sudden, I heard the honking and saw the movement. I could tell it was flapping wings by the thousands.

If I had been near a volcano, I would have been convinced that the white shapes ascending into the sky were the prelude of a large scale eruption. But I was in the middle of flat, uncultivated farmland. My first sighting was from a distance, and I could not identify what was happening. It was late afternoon, and the light was coming from a low side angle. Then, all of a sudden, I heard the honking and saw the movement. I could tell it was flapping wings by the thousands. North American first nation peoples had long observed the migration patterns of the Snow Geese. They gave them the name Chen Hyperboreus which means “from beyond the north.†They are breathtaking, pure-white birds with black wingtips. During the winter, when they feed in the fields north of Seattle, they take in a lot of iron, so you will find rust colors in the feathers on their heads. This coloration, while beautiful in itself, is just temporary.

North American first nation peoples had long observed the migration patterns of the Snow Geese. They gave them the name Chen Hyperboreus which means “from beyond the north.†They are breathtaking, pure-white birds with black wingtips. During the winter, when they feed in the fields north of Seattle, they take in a lot of iron, so you will find rust colors in the feathers on their heads. This coloration, while beautiful in itself, is just temporary. As is often the case, I hum or sing Goddess chants to complement what I am photographing. Majik-Norma Joyce’s chant recorded by Libana began to run through my head and across my lips – “We’re a river of birds in migration, a nation of women with wings.†This chant beautifully captures the essence of sisterhood and the momentum of the women’s spirituality movement. When I saw those thousands of birds I knew there was hope for the realignment of the world as women likewise fly together working for peace and justice.

As is often the case, I hum or sing Goddess chants to complement what I am photographing. Majik-Norma Joyce’s chant recorded by Libana began to run through my head and across my lips – “We’re a river of birds in migration, a nation of women with wings.†This chant beautifully captures the essence of sisterhood and the momentum of the women’s spirituality movement. When I saw those thousands of birds I knew there was hope for the realignment of the world as women likewise fly together working for peace and justice.

Recently I was walking among the tulip fields of Skagit Valley, WA, and it felt like being connected to a rainbow assortment of countless chalices or little Goddesses swaying in the afternoon breezes. Many mile-long fields of tulips are scattered throughout the valley as are the many events and activities that comprise a month-long tulip festival. The tulip fields are the crops of RoozenGaarde/Washington Bulb Co. and Tulip Town, and the fields are different each year due to crop rotation.

Recently I was walking among the tulip fields of Skagit Valley, WA, and it felt like being connected to a rainbow assortment of countless chalices or little Goddesses swaying in the afternoon breezes. Many mile-long fields of tulips are scattered throughout the valley as are the many events and activities that comprise a month-long tulip festival. The tulip fields are the crops of RoozenGaarde/Washington Bulb Co. and Tulip Town, and the fields are different each year due to crop rotation.